For 17 odd years Italy was promised a ‘liberal revolution’, but the man making the promises, three times prime minister and billionaire businessman Silvio Berlusconi did not deliver it. Then came Mario Monti – in November 2011 – and that more accurately labelled ‘neo-liberal’ programme commenced with haste. Twelve months of spending cuts, tax rises on the majority and deregulatory policies designed to slash wages and open up the public sector to private profit, followed. None of which made PM Monti popular, and he has now stepped down, to allow for parliamentary elections in February. Yet, whether the former European Commissioner stands or not – and that’s currently an open question – it’s looking pretty certain that his brutal free market policies will live on.

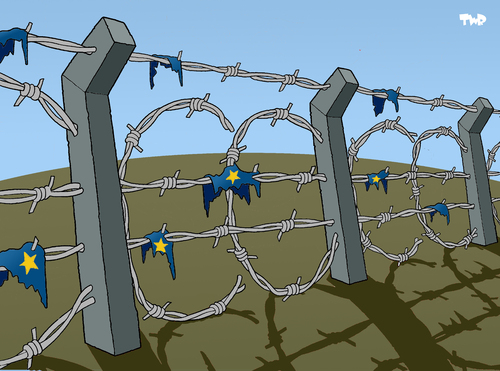

Leading in the opinion polls are the Democrats – comprising former communists and christian democrats. Leader Pier Luigi Bersani, confirmed as candidate for premier in recent US-style primaries, has pledged to stick to the self-defeating budgetary constraints pursued by Monti, which are now constitutionally binding after Italy signed up earlier this year to the EU’s Fiscal Compact treaty. The Democrats argue that they will add ‘jobs and equity’ to Monti’s programme, but unless they have a hidden plan to launch a unlikely reign of terror against the tax-dodging rich to find the funds for this, such a commitment is hollow, damning them politically, and leading Italy and the rest of Europe further down the austerity dead-end. They have also notably made no promise to restore employment rights Monti stole from workers.

Second in the polls is comedian-blogger Beppe Grillo, Italy’s version of the Pirates of northern Europe. Grillo has been a vocal critic of Monti’s austerity policies, and on paper his Five Star Movement has some progressive demands, from a referendum on the Euro and a rejection of any further loss of national sovereignty to a refusal to accept that the public purse should be raised to pay foreign banks. But, having spent years as a stand up act trailing round the country brilliantly exposing corrupt politicians of all political persuasions, Grillo is instinctively anti-government and anti-state. He appears to believe that slashing public spending on MPs perks and a clamp down on sleaze in general will fix Italy’s dire economic crisis. As Giorgio Cremaschi, a left-wing activist and leading figure in the metalworkers’ union FIOM, puts it, Grillo is going after the ‘chicken thieves’, not Monti’s friends in the corporations and banks lording it over Italy.

Then there’s Berlusconi, now in third place. He’s still trying, as Grillo does rather more convincingly, to play the role of an outsider in a political establishment widely despised by the Italians, although his media empire was the product of a very close relationship with former prime minister and embezzler Bettino Craxi. And since his 1994 entree into politics, he has presided over a new more virulent form of corruption in which corporations and the insatiable appetite for profit, instead of political parties pursuing illegal funding and their clientelistic policies, are at the root of sleaze. But this – and the continuing scandal of his control over three out of four private terrestrial TV stations let alone his influence via parliament over the state broadcaster – is not what makes him a figure of hate and derision among the global elite and the ‘free’ press that underpins it. Instead it’s because he’s (now!) anti-austerity and Eurosceptic, and dares speak the truth that Italy cannot for much longer continue in the Eurozone under the punishing conditions imposed by Monti and the EU.

Berlusconi fingers the high costs of sustaining Italy huge debt mountain, blaming the Germans and their ultra-prudent, Swabian housewife approach. Europe’s super-power, as the austerity ringleader and designer/enforcer of the Single Currency, is certainly a chief culprit in Italy deepening crisis. But Italy’s sky-high bond ‘spreads’ – the gap in interest charged on Italian debt compared to benchmark German government debt – are the result of speculation in the uncontrolled financial markets swelled by free trillions from the European Central Bank and the undeclared wealth of taxdodging companies in Italy and worldwide, and the world’s very well to do (like err…him). And traders can’t be faulted for their analysis of Italy’s deepening woes – it cannot sustain its debts if the economy isn’t growing (as has been the case for the last 12 years) or is going into reverse (as is the case now). But Berlusconi has revealed once again, with his dismissive remarks about how ‘spreads’ don’t really matter, that he doesn’t care about the economy or ordinary Italians. Instead what matter is his perennial legal difficulties, from tax fraud to child prostitution, and his business empire, and if he can gain advantage from ramping up latent anti-German sentiment – or for that matter abolishing a much hated new property tax – he will.

And then, trailing way behind in the polls is the fragmented political world to the left of the Democrats. A electoral pact under the name Cambiare di Puo (We Can Change) is desperately being put together, one that would weld former crusading anti-corruption and anti-mafia magistrates like Antonio Di Pietro together with some of the country’s most progressive mayors, greens and communists. But they too, if only to ensure agreement between the ideologically diverse factions, are ducking the central question essential for any return to growth, job creation and a reversal of falling living standards: whether they will reject Monti’s economically suicidal cap on public spending and the country’s humiliating and thoroughly undemocratic ‘supervision’ by unelected bureaucrats in Brussels and Frankfurt.

And so to former European Commissioner Monti, who replaced Berlusconi 13 months ago in a palace coup. As a member of the global elite’s secretive Bilderberg group, he is the ultimate guarantor in Italy of global capital, which would love to have him back at the helm. Not because of the kind of achievements you’d normally associate with a successful government, as unemployment, poverty, growth, public services and even debt levels are much worse than when he entered the premier’s residence in Rome’s Palazzo Chigi.

Monti also has fans on the Right, who feel betrayed by a man who instead of serving Italy’s rich and corporations in general, has just served himself. And they want a new leader. Some so-called ‘centrists’, who are really very right-wing former christian democrats, would back Monti too. Assorted high net worth individuals, like Ferrari boss Luca Di Montezemolo, too. Yet Monti’s popularity has plummeted since he got into power by the back door, and polls currently suggest the former Goldman Sachs advisor would probably trail in fourth place.

While Monti remains tight-lipped on his plans – which might involve riding out the elections and standing for President, a position that could allow him substantial power in the event of a weak government – the Democrats fear their chances of victory slipping away. And hence their increasingly desperate attempts to convince the ‘markets’ that they don’t need Monti because Monti’s legacy is safe in their hands. Which at least has the merit of consistency with their actions over the past year when they, together with Berlusconi (although he pretends otherwise), gave Monti parliamentary cover for the biggest attack on Italy’s working class and democracy since Benito Mussolini’s shock troops ruled the land.

Discussion

No comments yet.