It is possible to cut finance down to size and emerge from the crisis. To make the banks pay without falling foul of European rules. And even to convince the IMF of its strategy. Giacomo Gabbuti looks at the lessons from Iceland

While they were turning off the lights at that circus that is Davos, Iceland began the week on the right foot. At the World Economic Forum, President Olafur Ragnar Grimsson – described by the Al-Jazeera correspondent as “the only voice of hope” for a continent in recession – had given an interview to the Arabic satellite channel, sparking the interest of the network. To explain the “unorthodox” policies of his country, the president asked some simple questions: Why do we consider banks to be holy like churches? Why do we consider banks to be different from other “normal” companies, such as airlines and telecommunications firms. Why should we not allow them to fail? Why, above all, should we instead let the people fail, introducing new taxes and austerity measures, and not the banks, which have already benefited from the proceeds of those same risky assets that caused the crisis?

Answering Iceland’s President was the Court of EFTA – European Free Trade Association, an organization that brings together Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland. It was EFTA that in 1994 signed, along with members of the then EEC, an agreement that established the European Economic Area (EEA): it is by virtue of this treaty that Iceland – not a member of the European Union – is subjected to a large part of the EU rules, including those with respect to finance. The court, based in Luxembourg, was called upon to resolve a dispute (“Icesave”, the name of an online banking site) which began after the collapse of the Icelandic financial system in the fall of 2008. After the failure of the parent company of Icesave, Landsbanki Íslands – the leading Icelandic financial institution for over a century, responsible for the issue of banknotes until the establishment of the Central Bank in 1961 – Reykjavík refused to cover the losses incurred by Dutch and British branches of the bank.

As stated in the New York Times the Icelandic authorities had in fact twice tried to fulfil their obligations under Directive 94/19 of the European Commission, implemented via a special law passed by the Icelandic Parliament, which provides for a partial refund for savers. But twice the Icelandic voters, called to confirm the measures with a special referendum, rejected the proposal, refusing to pay taxes with debts incurred by private banks. As summarized in the press release issued by the EFTA Court, the British and Dutch authorities reacted as, required under their domestic legislation, by reimbursing their citizens. In particular, the British government had acted in a particularly strong fashion to the detriment to Icelandic national sovereignty, using anti-terrorism legislation to freeze the assets held in the United Kingdom by Landsbanki. To remedy this issue Iceland turned to the EFTA Court, which just last Monday issued its decision, in favour of Iceland.

According to the Court, European legislation before the crisis was not designed to anticipate systemic crises of the nature and extent of that seen in Iceland in the fall of 2008, and was not sufficiently clear on who would write off an entire financial system collapse. The record debts built up by 2008 by the Icelandic banks (commonly estimated according to the sources, between 9 and 12 times the GDP of the country in that year) made it physically impossible for the government repay all debts: for this reason, the possible precedent set by Icesave hung until Monday like a sword of Damocles over the country’s economic recovery.

In the absence of clear rules in this regard, the Court absolved the Icelandic government, which will continue its unorthodox policies, without imposing strict new taxes to pay off the debt of the banks. As Grimsson claimed in an interview to Al Jazeera, following the financial crisis, the Icelandic government did exactly the opposite of what is prescribed and carried out by the governments of the rest of Europe: after letting its banks collapse, it introduced controls on capital movements, has not – at least inot yet – introduced austerity measures, intervening in support of citizens left jobless and at risk of poverty by the sudden dissolution of their savings. But above all, as the NYT explains, unlike the United States and European countries – despite a thousand difficulties – the political and judicial authorities in Iceland have consistently worked to nail the managers responsible for the crisis. Which, continues the U.S. newspaper, gave the government sufficient authority with the Icelandic public to introduce the necessary measures to accelerate its exit from the IMF bailout programme. The IMF then had to publicly acknowledge the success of the policy in Iceland.

In claiming the success of this approach, President Grimsson made another, interesting statement: according to Grimsson, in fact, the basis of Iceland’s robust recovery is also the impact on innovation of a “sterilized” financial sector, small enough not only to not fail, but not to “drain” the brightest graduates in computer science, engineering, and even physics. Once banks were allowed to fail, these highly educated workers – protected from the risk of poverty by virtue of the strongly anti-cyclical fiscal and monetary policies pursued by Reykjavík – remained in Iceland to work, and have ended up reviving the real economy.

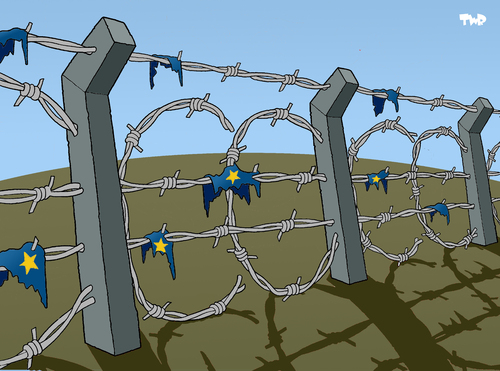

That is to say – as some Icelandic bloggers noted the Icelandic economic revival can be explained not by any particular foresight by its political class, but the stark impossibility of repaying its debts, and pressure from its citizens. One wonders if the “weakness” of Iceland – that is, the fact that is protected from European institutions – has, in fact, been its fortune.

www.sbilanciamoci.info

07.02.2013

Translation/Edit by Revolting Europe

Discussion

No comments yet.