By Jose Manuel Pureza

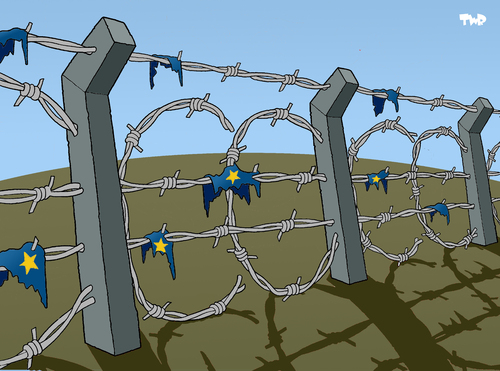

If there wasn’t the Troika there wouldn’t be money to pay salaries or pensions – this assertion is repeated ad nauseam by the heralds of foreign intervention in Portugal. And this is immediately followed by the argument that this is because we have long been living beyond our means, squandering money on health and welfare, on a bloated civil service or a swollen educational system.

The argument would have to be taken seriously of it were not doubly false.

First, because in a socially fragile country security and rights for the poorest is not fat, but muscle. Universal public services, the minimum wage and support for the unemployed and the least well off are not a luxury; they are minimum requirements of democracy and social cohesion.

Second, it is false because Troika intervention is a rescue of that part of the country that has always lived beyond the possibilities of the vast majority. To the austerity imposed on the poor and the middle class should be contrasted a country which is one Europe’s biggest markets for high-end cars, a country whose government is condoning the placement of capital in tax havens that institutionalise tax avoidance and a country where banks at risk of bankruptcy pay millionaire bonuses to executives.

At a time when people’s wages are being reduced, when the Troika is demanding that Portugal implement every eurocent of cuts announced reforms, a large Portuguese bank, Banif, decided to pay a bonus of 533,700 euros to one of its former managers in Brazil, adding to the 448,600 euros annual salary paid to him.

If Banif were simply a private bank like any other, and behaved in accordance with its statute, it would be a shocking episode, but nevertheless just a bad example. But Banif is a bank under state control; 1.1 billion euros has been injected into the bank and the state holds 99.2% of its capital. That the board of Banif has to uttered a word of criticism on behalf of the (almost) sole shareholder reveals the thinking of this shareholder when it comes to imposing limits on the excesses of those who always rode the wave of the crisis.

In the billionaire bonus of that Banif manager is synthesized the entire crisis: private debtors who have been saved, swelling the public debt, and the shift in the burden from shareholders to taxpayers, without the former losing even an ounce of their arrogance or being deprived of a raft of perks borne by the public purse. And meanwhile the state has even been sympathetic to, and complicit with those who run offshore accounts.

The Banif case is far from isolated: the CEOs of Portugal’s top 20 listed companies (PSI-20 index) received an average rise of 6% in 2012, a total of over 15 million euros. When in Portugal the average salaries of workers decreased by 7.2% in the same period, the conclusion can only be this: the crisis is the name given to the massive transfer of income from those who have always lived with less than they need, to those who have always lived beyond their means.

Esquerda.net

Translation/edit by Revolting Europe

Discussion

No comments yet.