To overcome economic crisis Spain needs an economic policy aimed at raising wages, among other measures. Just the opposite of the policy applied by the Popular Party, recommended by the Bank of Spain and imposed from the EU Troika, argues Fernando Luengo*

For reasons of equity. It is not fair that the costs of the economic crisis are borne by employees, for they have not caused it. Despite the rhetoric of the dominant discourse that insists that at the epicenter of the crisis is the growth of labour costs, fuelling the mantra that “we have all lived beyond our means”, the truth is that the crisis has been triggered by the excessive and disordered rise of finance, by excessive risk-taking by big players operating in global markets and the creation of a monetary union at the service of the financial industry, large transnational corporations and economies with greater competitive potential. Rather that excessive wage increases, it is the prolonged stagnation of wages over recent decades that is at the origin of the Great Recession. The result of limiting the purchasing power of workers and an increasingly strong concentration of income and wealth has fuelled a debt-based economy.

We must boost wages because, in recent years especially, many workers, especially those located in low skilled sectors where precarious forms of work prevail, have lost purchasing power: nominal wage levels have been reduced, the number of hours of unpaid overtime increase, the working day has been lengthened and rhythms of work have intensified.

Low wages don’t create jobs

It is time to end the policy of wage repression (euphemistically called internal devaluation) because, unlike what is claimed by the dominant forces in the economy, the downward adjustments in wages of workers does not create jobs. Quite the opposite, in a context of high public and private debt, reducing wages has had a contractionary effect, on both consumption and investment, with the consequent negative impact on employment levels.

It is time to reverse the trend of the relative loss of weight wages in national income which was already clearly visible in the last decade, but which has been accentuated in the years of crisis and has created determined that they progress in line with productivity; the connection of both variables is crucial for the revival of aggregate demand.

It is policies that aggravate deflationary wage repression that have seen in the Spanish economy the consumer price index located in a negative zone, which hampers the investment process and contributes to the increase in proportion to gross domestic product of public and private debt. It confines all economies in a loop from which it is difficult to escape.

Labour reforms

The latest labour reforms, the Gordian Knot called structural policies, promoted in particular by the Popular Party, have led to a substantial change in power relations for the benefit of capital over labour. By cutting the labour forces and imposing [downward] wage adjustments, businesses have received the wrong message: that lower labour costs are the way to improve productivity and competitiveness of the economy. This is far from the truth. This has led to business practices and a corporate culture that is conservative and adverse to innovation that in the best case scenario has only provided short-term returns, unsustainable in a longer time horizon.

Therefore, the repeal of the most recent labour reforms is one of the touchstones of a new economic policy, where wages have to play a new role. We urgently needs new labour institutions to restore the conditions for collective bargaining. Higher wages, better working conditions and democratized labour relations create the conditions and in fact are essential components of a new policy of labour supply, in sharp contrast to the wage restraint held up by economists and conservative governments.

Exports

Nor do results in external competitiveness justify wage adjustments because, as you know, the problems of the Spanish economy in this area goes far beyond the territory of wages, including prices, which are related rather to the existence of technological deficiencies, insufficient quality and sophistication of our exports and the heavy reliance on solid fuels in our production structure.

It should also be remembered that wage repression, the prescription in economic policy for all countries of the euro zone, has positioned exports as one of the main engines of growth, which creates a scenario of intense competition among countries committed to these policies. Yet it is impossible that everyone wins, because the exports of one country are the imports of others. Into this scenario have burst capitalist countries of the periphery and the former communist universe. The wage struggle in this context opens the door wide to an unstoppable degradation of working conditions.

Give greater weight to wages and, therefore, consumption in the form of aggregate demand – contributes to the correction of one of the macroeconomic imbalances that greatly threatens the operation and sustainability of the euro zone: the coexistence of large surpluses and current account deficits. Activation of demand in northern countries by way of rising wages (and government spending) would help reduce the German (and other surplus economies) surplus by increasing imports, reducing, in parallel, exports, and the correction of the deficit of the Spanish economy (and the other peripheral economies) as the markets where our goods and services are sold expand.

Public sector

The public sector has been a very prominent player in this process of creating job insecurity. To create the shift we need, our economy needs to play a new and active role, promoting a new framework for labour relations, increasing the minimum wage, strengthening labour inspectorates and incorporating into the folds of contracting with private companies clauses that prevent the downward modification of working conditions of its workers. In a broader sense, another wage (and employment) policy must engage the public sector in a policy aimed at reducing working hours and retirement age, the division of reproductive work with gender criteria via legislative action, and, of course, the restructuring and modernization of the productive fabric towards sustainability and an eco-energetic transition.

*Professor of Applied Economics at the Complutense University of Madrid and responsible for economy in the regional Citizen’s Council for Podemos

On Twitter @Fluengoe

El Publico

We are not more competitive by lowering wages – the data

One of the basic axioms which justified repression wage policies is that they are necessary to strengthen external competitiveness.

In broad strokes, the logic behind that statement can be summarized as follows. As labour costs are essential in the formation of prices, their impact containment acts positively on them, which puts companies in a better position than their rivals to export the goods and services they produce. The wage adjustment offers a competitive advantage that strengthens export capacities, resulting in higher market shares.

Accepting that logic means accepting four assumptions:

- Labour costs represent, in general, a decisive percentage of total costs of the companies.

- It assumes the existence of a linear relationship between the costs that businesses bear, labour and non-labour, and final prices at which market their output.

- Prices are central to defining the competitive position of business.

- This export-led growth model can be followed by all economies with similar chances of success.

It is not my objective here to examine the strength of these assumptions, which, despite their obvious weakness, theoretical and empirical, are robust from the point of view form conventional reasoning. It is a debate, however, economists and policy makers should not ignore, which if approached with rigor, could bring us closer to understanding the economy that really exists and provide tools to exit the crisis. That debate should cover such important aspects as the study of the mechanisms of price formation in business structures of oligopolistic profile, or factors other than labour cost and price in competitive strategies.

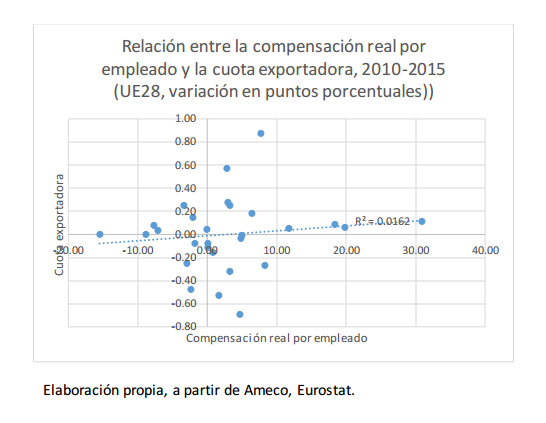

But now I just want to draw the reader’s attention to the following chart, relating to the group of countries that are part of the European Union (28 members) covering 2010-2015 the paths followed by real wages and market shares.

Returning to the logic of dominant reasoning of economists, mentioned at beginning of the text, those countries that have implemented stricter wage moderation policies, should have successfully defended or improved their export position. That is not, however, what the empirical evidence available suggest.

You simply cannot see that relationship, and, much less, the presumption of a link causal between wages (containment) and competitiveness (strengthening). If anything, the opposite – line of regression – follows a moderate upward trend.

At this crossroads, with data pointing in this direction, there are two alternatives.

First, to maintain, against all odds, the virtues of a wage policy applied with particular virulence in recent years (but which has already had extensive application in the EU). Justify policies that do not make us more competitive, do not take us out of the economic crisis and that only serve to feed a very conservative business culture.

Second, given that the achievements of the wage repression policies are limited and at best, of short duration, urgently engage social actors [eg unions] and the public authorities in a strategic discussion on the productive and technological shortcomings of Spanish business. And do not forget to give the centrality deserved in this debate mortgages and the limits of placing competitivness at the centre of our economic policy.

Translation by Revolting Europe

https://fernandoluengo.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/no-somos-mc3a1s-competitivos-bajando-los-salarios3.pdf

Discussion

No comments yet.