The unions questioned and challenged it time and again. Others who actually looked at the figures couldn’t under why. But the European Central Bank and the vast majority of Italy’s politicians were in agreement that a further ‘reform’ of the Italian pension system was absolutely indispensable.

And so it was in December that the government pushed through hefty hikes to the retirement age, to 66 by 2018, an end to indexation for pensions above EUR1,400 a month, and a move from earnings to contribution-based pensions. These amount to a €9bn ‘sacrifice’ by pensioners by 2014 alone. Elsa Fornero, welfare minister, who shed tears at the time, confessed that the state had ‘taken the hatchet’ to the pension system. Goldman Sachs said it was ‘the most important aspect’ of the Governnment’s austerity package.

But was it really necessary? It was interesting to hear representatives of the two main parties that backed these ’reforms’ address this question on the Italian radio yesterday.

Roberto Colaninno, a wealthy businessman and former minister for the centrist Democrats, said:

‘We mustn’t forget that this reform originated as a result of a delay that we have accumulated…and also the fact that in December we found ourselves with the risk that Italy would blow up, taking not only the pensions system but also savings and the future with it, and thus this reform was the result an accumulated delay and also a threat of financial collapse…without this reform there probably wouldn’t have been any pensions for anybody …we were retracing the steps, at a few months’ distance, of nearby Greece…these measures, that we can even define as brutal, allowed our country to escape from bankruptcy and collapse…to come out of intensive care and a deep coma.’

Alfredo Cazzola, another well-heeled businessman, and member of Silvio Berlusconi’s right-wing People of Freedom Party said:

‘I think the government has used pensions to send a strong signal to markets in Europe…the pension system itself had no major budgetary problems, however, let’s say when a country is tough on pensions, it gains credibility in international markets, that is, in reality, the pension [reforms] were a strong political signal that the Monti government wanted to send to the markets.’

Colaninno didn’t explain to listeners what was unsound about the previous pension system, nor what he meant by an ‘accumulation of delays’. For in truth, following earlier reforms the Italian pension system was already considerably ahead of Germany and France, in the sense that these earlier changes made it considerably meaner with the elderly. The reform was justified with an “unless …” and an “if …”: that old weapon of fear. Italian citizens had accept unnecessary, hasty and unfair reforms, lest they end up like the Greeks.

Cazzola didn’t even bother pretending that changes were needed to improve the soundness of the retirement system. As he said, it ‘did not in itself had major budgetary problems’ . Instead the real inspiration was to gain credibility with international speculators. The retired and retiring, he was clearly saying, were used as bargaining chips to cut bond spreads.

And that’s about it. Nothing to do with the government’s stated aims of a fairer burden between the generations, or putting the pension system on a sustainable footing.

The state pension fund was seen as an easy target to raid in order to patch up the public finances ruined by years of growth-destroying austerity policies and decades in which the state had been a soft touch on the rich and big business.

Could the Government have chosen another target?

Like tax dodgers who rob the state of more than €120 billion a year.

Or owners of yachts, ferraris, and vast property and share portfolios who won’t go hungry or be left homeless, or even miss a holiday if they each parted with some of their millions to help restore the public coffers? That 10% with 46% of Italy’s great riches, the few thousand families who own a sizeable chunk of the €9.5 trillion in assets known as household wealth. Yes, they could.

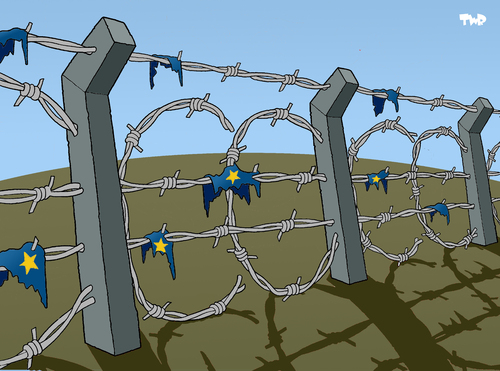

But for plutocrat Monti and his cabinet of millionaires it was simply easier to rob the powerless and now even more penniless pensioners. And cover it up with a big lie.

Discussion

No comments yet.