When launched in 2005, primary contests seemed like a good idea to help revive the Italian centre-left’s flagging fortunes and divisions at a time when Silvio Berlusconi’s grip on power appeared unassailable.

Over 4.3 million people took part in contest for the leader of the Union alliance that gave overwhelming backing to former premier and European Union President Romano Prodi and helped project the Left back into power. Two years later, in October 2007, as the social democratic Left Democrats merged with the Margherita, a coalition of christian democrat and centrist parties, to form the Democrats, a primaries contest galvanized 3.5 million people to elect a new leader, Walter Veltroni, former Mayor of Rome. Fast forward another two years, and Pier Luigi Bersani was elected leader of Italy’s second largest party with just over 50% share of the 3 million votes cast.

Measured by levels of participation, involving party and non-party members in selecting the centre-left leader was a great success. But judged by the yardstick of making a decisive change to the fortunes of the Left, the picture is more mixed. Although the enthusiasm around that first foray into the primaries game helped get the Left back into government, Prodi’s second administration lasted just 19 months, no longer than the previous spell of May 1996-October 1997. And clearly, a new leader every two years on average is not to be celebrated.

But at a local and regional level, particularly since the financial crisis of 2008 hit the shores of the peninsula, some exciting developments have been taking place within the centre-left as one outsider after another has challenged and defeated the Democrats leadership’s often grey and tired favourites amid some really energising campaigns. And the vast majority have been of a distinctly radical hue.

Even before Prodi was projected by popular will to the number one spot, gay, communist MP and anti-mafia campaigner Nichi Vendola challenged the Democrats’ choice – right-winger Francesco Boccia – as candidate for Governor of the conservative and strongly Catholic southern region of Puglia.

Not only did Vendola beat Boccia but he went on to take-out in April 2005 the outgoing president Raffaele Fitto, from Berlusconi’s coalition. In 2010, Vendola again stood against Boccia and the Democrats party machine and went on win the governor election with an increased share of the vote.

Next came the traditional right-wing stronghold of Milan, where in November 2010 Giuliano Pisapia, a long time communist, threw his hat into the ring in the teeth of opposition from the Democrats. Backed by prominent intellectuals and figures from the world of culture, and a highly visible grassroots campaign, Pisapia boxed his way to victory in the primaries and subsequent mayoral election in a shock defeat for a key Berlusconi ally, the incumbent Letizia Moratti.

In the same mayoral elections in spring last year, radical former magistrate Luigi Di Magistris led a barnstorming campaign to become the number one citizen in Naples, clawing back credibility for the Left tarnished by corruption scandals; and in the Sardinian capital Cagliari progressive Massimo Zedda was victor in a campaign squaring up to powerful construction and tourism interests close to Berlusconi.

And finally, in February there was the victory in primaries in Genoa of university professor Marco Doria, who shares with Vendola, years of activism in the communist party.

This American-style system of choosing leaders and candidates has always had its critics, rightly fearful that it undermines the role of party activists. But in Italy, as elsewhere in Europe, social democrat parties’ ‘modernising’ efforts have for the large part already hollowed out internal democratic processes from within, replacing them with a top-down, media-obsessed and personality-based politics ever more distant from their traditional working class voters.

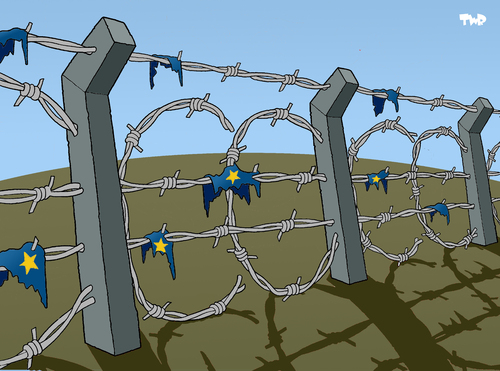

And in Italy, since the once mighty Italian Communist Party dissolved itself after the Berlin Wall came down, giving birth to the PDS (a precursor to the Democrats) on the one hand and a myriad of parties to its left, the divided Left has had to form coalitions as a means of gaining power. Against this background, the primaries process has curtailed damaging party political competition while giving activists from a wide political spectrum with a common interest in victory for the Left some ownership over the choice of leadership. For the Democrats in particular, primaries have provided a healthy alternative to corrupt horse trading between politically indistinguishable party elites.

Most importantly, though, the campaigns around fresh, radical ideas have energised a Left that ditched marxism 20 years ago but found nothing to replace it, except an eternal search for the political middle ground. This shake-up could eventually reach to the top: Governor Vendola, more popular and arguably more charismatic than any of the current crop of Democrat leaders, is eying the job of candidate-premier.

This is all deeply worrying for the right-wing barons of the Democrats and a break-up of the five- year old alliance of former communists and former christian democrats is a strong possibility. Still, this is nothing compared to electoral risks the Democrats’ are running by continuing to support Mario Monti’s ‘technical’ government as it proceeds with an unprecedented attack on living standards, labour rights and Italy’s cherished welfare state.

Discussion

No comments yet.