IN THE RADICAL PRESS / MUNDO OBRERO

By Mariano Asenjo Pajares

Cinecittà, the largest film studios in Europe, the dream factory on the banks of the Tiber, is on the verge of disappearing…

The crisis, cuts and a steady erosion of culture are threatening to close Italy’s mythical Cinecittà studios. They are to be replaced by a large hotel complex, health clubs, a giant car park and a theme park dedicated to the movies.

The plans involve many layoffs – and a juicy opportunity for speculation. From July 4 a number of workers, together with their unions, have been protesting under the banner “Cinecittà Okkupata” and demanding a rethink of the project.

The plans will be the coup de grace for the site’s treasured cultural heritage that for almost 80 years shot scenes for more than 3,000 films. Cinecittà hosted the filming of classics such as Ben-Hur, La Dolce Vita, Cleopatra, Quo Vadis? and most recently films like the third installment of Mission Impossible and Gangs of New York. Delivering 37 Oscars, the studios were Fellini’s favourite, and the central production house for Roberto Rossellini, Federico Fellini, Vittorio De Sica and Luchino Visconti.

Fascist origins

It was in 1935 that the Italian Fascist regime created the Centre of Experimental Cinematrography, and two years later Mussolini inaugurated Cinecittà. Realizing the importance of film as a means of prestige and propaganda, the Duce put his son, Vittorio, in charge of the influential magazine Cinema, the ‘Organ of the Fascist Federation of Entertainment’ with a circulation of 20,000. In practice, both the magazine and the Centre of Experimental Cinematography became a hotbed for anti-fascists, including many members of the Communist Party. It was where postwar Italian film directors like Michelangelo Antonioni or Giuseppe de Santis were trained.

Mussolini shocked and surprised all by inviting French director Jean Renoir, a director close to France’s Popular Front, to make movies in Italy despite his communist sympathies, and the banning of several of his films. He was offered the opportunity to shoot an adaptation of Puccini’s Tosca. Renoir, after the unfavourable reception of ‘The Rules of the Game’, was ready to accept any project.

Communist influence

Renoir included in his project, as assistant director, Visconti, another name linked to Cinecittà and the Italian Communist Party (PCI ), which he always supported in elections but never joined. Years later, it was the PCI which always defended Visconti, who was the closest to Marxism within the Italian neorealist school and who in his films represented the problems with censorship in the new democratic Italy. Arising from that relationship, before the 1948 elections Visconti accepted the party’s commission to produce a documentary that showed, with unrelenting realism and rawness, the miserable living conditions of the people of southern Italy.

Another name that guides us through the story of the iconic film studios and PCI is Giuseppe De Santis, who during the 1940s attended the Experimental Center of Cinematography, where he graduated with flying colours and where he could make his first forays into film directing. By that time, he had became acquainted with a large group of young Romans already involved in clandestine antifascist struggle, among whom was Pietro Ingrao, one of the politicians and leading communist intellectuals of the twentieth century and who, outraged by Franco’s attack on the Spanish Republic, was part of the underground Liberation army that participated in the arrests of fascists and Nazis in Rome.

Censorship

Ingrao, poet and film buff, was a screenwriter and assistant director for Visconti’s Obsession, an adaptation of the novel by James M. Cain, The Postman Always Rings Twice, that was set in Italy. The premiere of the film in 1943 was a major scandal in Fascist Italy: it was stolen, scenes butchered, and the original destroyed; its treatment reached such absurd heights as an archbishop blessing a room where they had shown the film in order to ‘purify’ the sin committed therein.

Returning to Giuseppe de Santis… That group of young Roman antifascists determined his political orientation, because as a PCI militant he had responsibility for deading with the issues faced by the working class and peasantry. His first feature film Tragic Hunt (1948), reflecting the struggle between the peasants in a cooperative and a group of landowners, initiated the era of neo-realism, which De Santis contributed to through a rigorous analysis of the social forces at play and his ability to capture human and social reality, as it was. These characteristics are largely responsible for the success of his next film, Bitter Rice (1949), which narrates, with the interpretation of Silvana Mangano, the hard and precarious life of rice pickers, in a story that combines political analysis with a depiction of the class struggle of the time. Browsing the filmography of Giuseppe de Santis we find Attack and Retreat (1964), a co-production between Italy and the Soviet Union on the withdrawal of Italian troops from the eastern front in the Second World War and the rebellion of workers on both sides against the war.

Cold War bonus

After World War II, against the backdrop of the global hegemony of Hollywood and the Cold War, Cinecittà enjoyed the favour of the Americans who were anxious, at all costs, to prevent the rise of the Italian Communist Party. Such was the scale of US investment that Cinecittà became known as Hollywood on the Tiber, with the studios and luxury hotels of Via Veneto graced with the likes of Gregory Peck, Rock Hudson, Charlton Heston, Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Clark Gable, Jennifer Jones, Audrey Hepburn, Errol Flynn, Kirk Douglas and Ava Gardner.

The end of the Cold War left its mark not only on the political, ideological, economic, social, technological, military and sporting field, but in the world of culture too.

‘They want to build hotels, swimming pools and theme parks to attract the foreign productions – absurd, as if Rome didn’t have hotels,’ said one of Cinecittà workers recently. They have also announced the outsourcing and cuts to jobs. ‘Cinecitta has 75 years of history, from here more than 3,000 films have been produced and 37 have been awarded an Oscar. It’s not something you can forget overnight. To let this become a resort is bleak,’ reads one statement by the affected workers.

Federico Fellini said of Cinecittà: ‘I have called it the dream factory, a bit banal but true. It is a place that should be looked upon with respect, because beyond these walls are gifted and inspired artists who dream for us. For me it is the ideal place. The cosmic void before the Big Bang. “

Campaign to defend the studios

The Communist Refoundation Party has pledged to ‘support the workers who have occupied Cinecittà, defending not only their jobs but also the function Cinecittà has always played for Italian cinema and the cinema in general.’

‘This government is demolishing the social state and Italian culture. Research institutes are closed, 200 million euros are cut from state universities and given to private schools. This is a government that does nothing to prevent the dismantling of Cinecittà and does nothing in defense of Italian culture, which is one of the most important resources for economic growth and social development of this country and to democracy itself.’

A group of Italian filmmakers including Ettore Scola, Bernardo Bertolucci, Giuseppe Tornatore and Marco Bellochio and joined by Ken Loach have signed a manifesto to the President of the Consiglio, Monti, and the Republic Napolitano, called on Cinecitta to be saved.

Their French colleagues, including Lelouch, Beneix, Costa-Gavras, Tavernier and Hazanavicious have been even more outspoken in their protests. ‘Is it urgent to destroy this place inseparable from the cinema of Fellini, Visconti, Comencini and Lattuada, amongst others, in order to build a fitness center?” they said in a petition, that continued, ‘Even under [premier Silvio] Berlusconi, they didn’t dare,’ r.

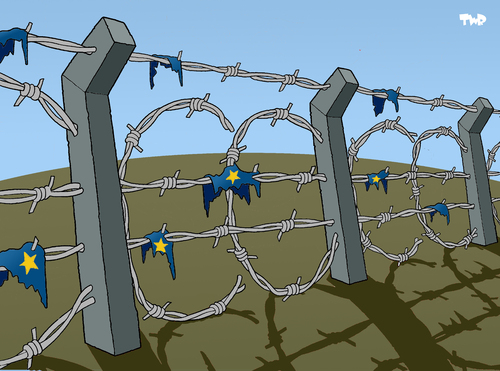

In a recent humorous vignette hinting at the struggle of the legendary Italian studios to save themselves from closure says: “You have already stolen our dreams. Now they want to take away the factory where they are manufactured. Save Cinecittà! “

El Mundo Obrero 18 Sep 12

Campaign backgrounder:

For some two months lighting engineers, set builders and other workers have been camped day and night on the roof of the main gatehouse of the studios. The workers believe the changes planned by management mark the beginning of the end of the studios. Production continues with nearly 20 foreign and Italian TV projects, but competition on cost is growing from eastern Europe and the last big movies, like Mel Gibson’s The Passion of Christ and Martin Scorsese’s The Gangs of New York, were shot some eight-ten years ago.

Hence the management’s plans. But the workers fear that in the years ahead the valuable real estate on which the studios were built will be sold off to property developers, and that finally Cinecitta might disappear.

Ken Loach, Vanessa Redgrave, Bernardo Bertolucci, Costantinos Costa Gavras, Gianni Amelio, Marco Bellocchio, Ugo Gregoretti, Citto Maselli, Franco Nero, Pasquale Scimeca, Ettore Scola, Bertrand Tavernier and Giuseppe Tornatore wrote to the Italian President Giorgio Napolitano and Prime Minister Mario Monti in July calling on them ‘to urgently intervene’ to stop the plans and to restore Cinecittà as ‘a central production site for world cinema and its public role as a driving force for the renewal and revitalization of Italian cinema.’

With the deepening economic crisis, misery and poverty in Italy and Europe – little of which is reflected on the big screen – that renewal might even involve a rediscovery of the golden years of neo-realism…

Discussion

No comments yet.