By Vincente Navarro

Given the enormous financial and economic crisis prevailing in Spain, there are three alternatives. One is to continue the austerity policies of the Popular Party government, following the instructions of the European Council (dominated by conservatives and liberals) of the European Commission (the clear conservative neoliberal orientation) and the European Central Bank (under the enormous influence of the Bundesbank , Germany’s central bank, which has been defined with reasonable certainty, and ironically, as the Vatican of neoliberalism), exponent of German banking.

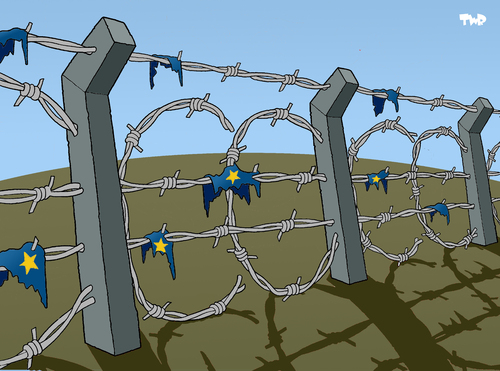

These policies inevitably lead to a recession, bordering on depression, for many years. Their centrepiece is a frontal attack on the world of work, the welfare state and democracy. The evidence for that is robust and overwhelming. Its highest expression is what is happening to Greece. Behind this strategy is financial capital (which now dominates the behaviour, not only financial but also economic, in the Eurozone) and the capital of large companies. This option is, without doubt, the worst. To expect ‘expansionary austerity’ policies to be effective in stimulating the economy to bring it out of recession belongs to the realm of neoliberal dogma that has been long accepted by left leaders and which is leading Spain, Europe and the world into disaster.

Another alternative is to follow policies that are almost the opposite to austerity. This alternative would be inspired by the expansionary policies of the New Deal in the early twentieth century in the U.S. and also by the expansionary policies of the fifties and sixties that most countries followed in Europe, stimulated by the Marshall Plan. Such expansionary policies, carried out on both sides of the Atlantic, allowed U.S. and Western Europe come out of the Great Depression. The application of such policies in Spain and the EU would be a large increase in public spending that would aim to create jobs and, through it, to increase domestic demand and stimulate the economy. Such policies would have at their heart growth promotion, both of Spain, and at the level of the EU. Contrary to conventional wisdom, this strategy would be feasible in terms of bring growth even to Spain, even when their performance would be simpler if such policies were also performed at the level of the euro area and the EU.

They tell me that the French government has already started along this path. But, as I wrote recently, the Spanish government has signed the Fiscal Compact that requires States to have balanced budgets, without even questioning the Stability Pact, which is what is determining the massive public spending cuts being made in the Eurozone countries. They can not develop growth policies without questioning such agreements. The fact that the French socialist government has just proposed to the French Parliament to approve such a Fiscal Pact is an indicator of the improbability that such an alternative expansionism will take place in that country.

I’m not ruling out that with the growing popular protests, led by trade unions, and the growth of the left parties to the left of the ruling social democratic parties, the latter will move towards positions more consistent with their pro-growth discourse. But this remains to be seen. I’m not ruling it out (and that would be my personal preference), but I am skeptical. Social democratic parties have not undergone the self-criticism needed to make a very substantial change in their economic policies. Spanish and Catalan social democracy are clear examples. The economic policies being proposed assume that the economy will recover on the basis of increased exports, when the key element of recovery will have to be through an increase in domestic demand.

This brings us to the third alternative, which is not my first choice, but I believe more than ever the only option left, since, as I said before, the worst option is to continue with the current situation. And the third option is Spain leaving the euro. I reached this conclusion because I understand that Spain does not have the tools and instruments to overcome the crisis. You cannot devalue the currency to make Spain more competitive, and the state cannot protect itself from financial speculation as it does not have a central bank. This is intolerable. Unless Spain regains these tools, in the current framework of the eurozone, it cannot recover. Actually, it is no coincidence that Britain and Sweden are starting expansionary policies, as both countries have their own currencies and their own central banks.

The arguments that have been deployed against such exit euro in most of the media are so biased that they lack credibility. Let’s examine them.

One is that Spain, by leaving the euro, would have closed off the possibility of borrowing money in the financial markets. The same argument was used, of course, with many countries, including Argentina (when the dollar was removed), without the reality corroborating such an assertion.

Today’s financial system is multipolar, and there’s no shortage in the world today of cash or credit. On the contrary. Today the world is awash with money. There is an excessive accumulation of financial capital. The problem is lack of demand from most populations. Such scarcity is artificially created in Spain (and designed from scratch by the creators of the euro and the ECB). Today Spain could get credit at much lower interest if not in the euro. Sweden and Britain, both in the EU but not the eurozone, have no difficulty in obtaining credit.

Another argument that has been used is based on the ignorance of some facts. It has been said many times that Argentina managed to recover so soon (it only needed six months to return to growth after breaking with the dollar) as a result of the high demand for natural products in a very expansive global economy. This argument ignores the fact that Argentina’s recovery was not based on export growth, but growth in domestic demand.

An argument that has more validity, however, is the risk of rising inflation, a result of a central bank printing money to support many expansionary policies. This risk is real. Now, between two lesser evils, high inflation is preferable, alongside low unemployment and high growth, to the current situation, of low growth, high unemployment, and recession.

I admit that leaving the euro would not be an easy process. But this argument-the difficulty of leaving the euro- must be considered in light of the human, economic and social costs of staying in the euro.

Proposals to get out of the crisis within the euro, based on increasing exports (as being proposed, not only by the economic teams of the Popular Party, but also the Socialists and Catalan Socialist Party – PSC), ignored (I repeat what I said before) the biggest problem of the Spanish economy is the huge fall in domestic demand. As I have emphasized, the export sector has been growing in Spain, while the economy has been collapsing, year after year.

The solution is an increase in demand that cannot be delivered unless there is a break with the policies imposed by the authorities in the eurozone and the IMF. Interestingly, the two states mentioned above, the British and Swedish (both governed by conservative parties) have concluded that without expansionary policies, economic stimulus, they cannot recover from the downturn. But as I said before, both can do it because they have their own central bank and their own currency. Hence, even though the British debt is greater than the Spanish (which is relatively low), interest on public debt are much lower, and neither, Britain and Sweden, have high inflation. The fact that there would be a risk of high inflation need not lead us to conclude that there will be high inflation affecting the efficiency of the Spanish economy.

One last observation. It shows great stupidity that none of the two major parties capable of governing Spain have threatened to pull out of the euro. The last thing that Germany and its banks want is for Spain to leave the euro. The Spanish State should use this threat as a bargaining chip in negotiating their discussions with the Troika. The fact that it does not shows just how much Spain is a dependent state.

Vincente Navarro is Professor of Public Policy, Pompeu Fabra University, Spain, and Professor of Public Policy, Johns Hopkins University, US

Salirse del euro El Publico

27 Sep 2012

Translation Revolting Europe

Discussion

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

Pingback: Euro Crisis: A Roundup of the Week’s Opinions « Marko Polo Travels - October 3, 2012