Footloose, unaccountable global finance, privatization and a justice system that’s soft on white collar crime: these are the roots of the rising tide of sleaze in Spain and elsewhere. Governments must stop providing the corrupt with the weapons to commit their crimes says Juan Torres López

Corruption is an old phenomenon and is spread throughout the world. It has attracted the attention of many social scientists and the condemnation of political leaders of all colours. But it hasn’t been eliminated. Conversely, it has been increasing in the last three or four decades.

Perhaps this happens because in tackling it, you seek fixes based on beliefs or ideological prejudices rather than looking at the facts from the least corrupt countries.

Thus, in recent years the prevailing idea is that corruption is something linked to the public sector itself, and is greater the larger the public sector presence in social life and, therefore, what you have to do to is to reduce the public sector to a minimum.

It’s a liberal idea with deep roots but it does not sit well with the facts. There are a multitude of cases, such as Enron, the Spanish electricity companies, the credit rating agencies, or banks that with their scams caused the current crisis, that shows that corruption is also widespread in the private sector.

It is also a fact that corruption has skyrocketed in recent years precisely in countries such as Russia and other Eastern European economies that have replaced economies dominated by the state to those dominated by the market, or where there have been out a large number of privatizations. And it often appears to be the case that the vast majority of the least corrupt countries (in 2012, Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, Sweden …, according to Transparency International) are themselves among those with a higher volume of public spending in relation to GDP, or those which have more public employees as a proportion of the workforce.

Therefore, it is not a rigorous argument to say that by the simple expedient of reducing public sector activity or the number of public employees, as lately it has been proposed also in Spain, we can eliminate the corruption from which we currently suffer.

Instead of starting from ideological premises, it would be better to learn from the least corrupt countries. Like Finland, for example. Paula and Seppo Tiihonen give various reasons to explain why in his country there are few cases of corruption. Among them, equality, prestige and good compensation for officials, public funding of parties, transparency, duty to publicly justify the reasons for decisions, the power of the ombudsman, the structure of collective and collegiate decision making, or personal independence and responsibility.

In any case, all this would not be enough to end corruption. There should be laws that prevent governments providing the corrupt with the weapons to commit their crimes. It is an aberration that the Spanish state is the one that provides the phone lines to Gibraltar where the corrupt launder their money, laws are enacted as the Land Law without an independent authority assess its real impact, or that the government privatizes public wealth without checks and balances to gauge how it’s done and the resultant costs and benefits to society.

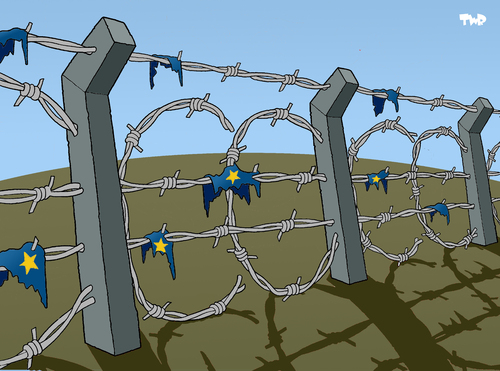

Tax havens, banking secrecy and the full capital mobility are the factors that have encouraged and enabled large-scale corruption. Without them, the corrupt would be more easily controlled. While they exist the profits of their crimes will always be safe. You have to end them.

It is also essential to have a criminal justice system that works. And we need to be much more watchful of the watchdogs: it can not be that Bank of Spain inspectors report, passively and compliantly, the behaviour of their directors and yet no action is taken against them. It is a joke to say that you are fighting corruption while many crimes of this nature end up being timed out, when you see generous pardons of hundreds of politicians, businessmen and corrupt bankers, transgressing judges, fraudsters and drug traffickers. Or when there are dozens of thousands of people swindled by banks and not one banker in jail.

Juan Torres López is Professor of Applied Economics at the University of Seville

nuevatribuna.es February 25, 2013

Translation by Revolting Europe

Discussion

No comments yet.