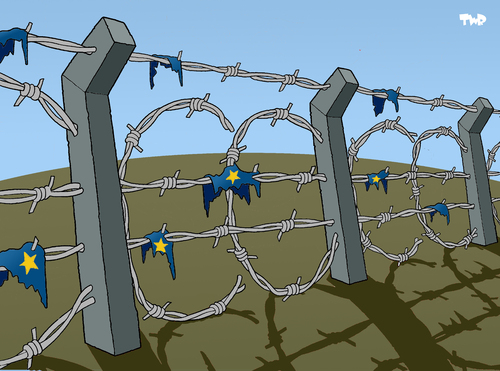

Why Merkel has no choice to pursue austerity in Europe, despite its catastrophic social and economic consequences. And to save Europe, the Eurozone must be ditched. By Jacques Sapir

Thanks to the combined effect of austerity policies, the Eurozone is sinking into crisis. Yet never have debates on economic policy been so intense. Political leaders, both Germany and France and other countries, however, are deeply wedded to austerity.

Unemployment in the Eurozone is now 12% of the labour force, with peaks of over 25% in Spain and Greece. Economic activity continues to decline in Spain, Italy and Portugal, and now consumer spending is starting to collapse in France, pointing to a further deterioration of the short-term economic situation.

The second largest country in the euro zone, France, had until recent months avoided the worst in the Euro zone by virtue of the strength of consumer spending. But if the decline seen since January continues, the consequences will be significant, both in France and in neighbouring countries, and in the first place in Italy and Spain.

Europe’s austerity dead end

The general deterioration of the economic situation highlights the problem of austerity adopted by all countries since 2011, following Greece, which had been forced by the European Union, then Portugal and Spain. But Germany’s determination to continue with austerity is clear, and it has recently been reaffirmed. Why, then, such stubbornness? First there is the obvious national interests.

The euro area delivers to Germany about 3 percentage points of GDP per year, either through the trade surplus, which is achieved 60% at the expense of its partners in the euro zone, or through the induced effects of exports. It is perfectly understandable that, in these conditions, Germany is favourable the existence of the eurozone. But if Berlin wanted the euro zone to work as it should, it would have to accept the transition to a

comprehensive fiscal federalism and a transfer union.

But if Germany were to accept this federalism, then it should accept, as a result, the transfer of a large part of his wealth to its partners. Just to bring savings in Spain, Greece, Italy and Portugal, to the levels prevailing in Germany and France would account for transfers of between 245 and 260 billion euros, between 8 and 10

percentage points of GDP, every year for at least ten years.

Sums of this scale – and it is not impossible that they could be even higher – are absolutely outrageous. Germany could not afford such an amount without jeopardizing its economic model and destroying its pension system. It therefore wishes to retain the benefits of the euro zone, but without paying the price. That is why it has always rejected the idea of a “transfer union’. Beyond that, the problem is not so much that Germany “wants” or “does not want”, it is what so it can bear that matters. And it cannot bear a levy of 8% to 10 of its wealth. So let’s stop thinking that “Germany will pay,” an old refrain of the French policy which dates back to the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, and instead look at reality.

Germany already has already displayed a significant degree of reluctance on banking union, although she accepted it in autumn 2012. Germany’s Minister of Finance has just said she considered that it is through an amendment to the existing treaties that banking union could emerge. It is certainly possible to modify the original texts, but everyone is aware that it will take time.

Germany is pushing for the introduction of the banking union, in 2015, and most likely 2016. And what of Germany’s concerns about the “constitutionality” of banking union? Merkel has some good reasons for wanting to ensure perfectly legal texts: the recent creation of new Eurosceptic party “Alternative for Germany”, a party that polls currently put at 24% of the vote, is a credible threat to the political balance in

Germany.

Under these conditions, there is no other choice for Germany to defend a policy of austerity for the euro zone, despite the absolutely catastrophic economic and social consequences that this policy creates.

Austerity’s disastrous consequences

All countries, one after the other, are engaged in suicidal policies of internal devaluation that are the equivalent of the deflationary policies of the thirties that brought Hitler to power. This is the case in Spain and Greece, where unemployment and austerity devastate society.

But these are not the only consequences. Austerity is pitting the people of one nation against the other. The paradox here is total. Europe, usually presented as a factor of peace on the continent, now turns out to be aggravating conflict and reviving old hatreds.

In the case of France, the consequences of austerity are clear. If you are determined to reduce the cost of labour to try to restore industry competitiveness without devaluing, it is clear that this will drive down wages and contributory welfare benefits. But then consumer spending, which has already fallen, will collapse. Inevitably we will see the impact on growth and now the most credible estimates indicate that the French economy in 2013 will stagnate at best and more likely contract by -0.4% of GDP. The latest IMF, too, has greatly reduced its projections for growth in 2013. A difference of 0.4% of GDP between the forecasts made in January and those made in April demonstrates the reality of the direction in which France is heading.

The result will of course be a significant rise in unemployment. If we want to reduce our costs by 20%, we will probably increase unemployment by half, sending the jobless rate to more than 15% of the working population, or 4.5 million (or indeed 7.5 million if you include all the ministry of labour’s categories of unemployed). In addition, in the euro area, Spain and Italy are already competing with France through wage deflation.

Moreover, and even more significantly worrying is that corporate profits and business investment are collapsing. This implies that the modernization of the productive apparatus will fall behind and that what we might win through policies of internal devaluation, we would lose in productivity.

Hollande hoping for the cavalry

To date, our leaders, especially in France, are hoping to weather the storm. President François Hollande is putting all his hopes in a hypothetical US recovery to reduce the weight of the burden of austerity. However, he has already had to admit that this will not occur in the second half of 2013, as he had initially announced, and he has shifted his forecast of a recovery occurring in early 2014. But, the US recovery continues to shift. It

is an illusion to believe that external demand will now save the day. US growth is lower than expected, with the IMF reducing its forecast. As for China’s growth, it slows from month to month. François Hollande hopes that we will be saved by the cavalry, but the cavalry is not coming.

Add to this the fact that the calculations made by the government in 2014 are singularly unreliable. The government maintains its budget deficit target for 2014 of 2.9% of GDP. However, we are not in 2013 and its not at 3%, but 3.7% (at best) or 3.9% (at worst). A reduction in the deficit of 0.8% to 1% implies budget savings or the release of new fiscal resources worth 16-20 billion euros. But such a tax burden, given a multiplier of government spending that is most likely to 1.4 (if not more) will result in a decrease in

economic activity of 22.4 and 28 billion euros. This will result in a fall in tax revenues of between 10.3 to 12.9 billion euros. The total gain of budgetary measures and / or taxes will be more than 5.7 to 7,100,000,000. If the government intends to achieve, at all costs, the deficit target it has set, it will have to reduce spending, or raise levies by € 45 billion, not 16 billion euros as originally planned.

But this levy amounting to 2.25% of GDP will then lead to a decline in economic activity of about 3.1%. Given that the growth forecast by the government is 1.2% of GDP for 2014, this will mean, that is, if the forecast is reliable, a recession of -1.9% of GDP. If the government is content with a cut in spending or increase in taxes of 16 billion euros, the negative effect on growth will be “only” 22.4 billion euros, or 1.1% of GDP, and in 2014 we will see an effective growth of just 0.1%, and a deficit of 3.5%. These calculations demonstrate the futility of austerity under current conditions.

The future of the Eurozone

More than ever, this raises questions about whether the euro zone can survive. The problems of countries as diverse as Greece, Spain, Portugal and Italy will converge in the short term, probably during the summer of 2013. In these countries the fiscal crisis (Greece, Italy), the economic crisis, the banking crisis (Spain, Italy) is now developing in parallel. It is therefore highly likely that we will experience a severe crisis in the

summer of 2013 or the beginning of autumn. It is time to settle accounts. The Euro did not create the growth that was expected when it was created. It is now a cancer in the heart of Europe. If we want to save the European idea while there is still time, we must quickly dissolve the euro area. Leaders from various political parties should come together around this solution. However, it however necessary to act quickly. Time is

short.

Russeurope April 20, 2013

Translation/edit by Revolting Europe

Discussion

No comments yet.