As the financial crisis accelerates in Spain, resistance to austerity is growing

Spain is living through the sharpest period of unrest in a generation. Mass protest is now a daily fact of life. Millions having filled the streets and plazas. Job centres and mines have been occupied, and roads blocked. Thousands have marched on the capital from the coal mines of north and north east, and Andalucia in the south. Workers have even tried to storm government offices and parliament. Civil servants, teachers, students, health workers, firefighters, miners, the unemployed and now even the police have joined the revolt.

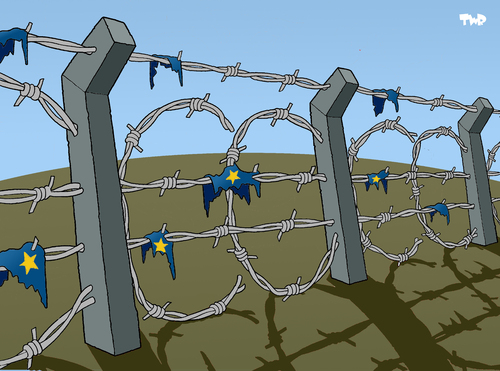

The popular anger reached boiling point mid July when the 8-month old government of Mariano Rajoy applied yet another viscious turn of the austerity screw . A further €65bn (£50.6bn) of spending cuts and tax rises – designed to meet deficit targets set by Brussels – were unveiled and approved within a week.

And all while finance ministers from the single currency’s major economies approved a €100bn (£77.8bn) hand out to Spain’s banks, the very institutions who set off Spain’s economic meltdown when a property bubble that they fuelled burst.

Rajoy, who has broken practically every election promise he made, including not to raise regressive, recessionary taxes like VAT, is doing is best to ignore the popular rage that has spilled out into the country’s streets.

Austerity isn’t working

But his problem is that his austerity policies are not working. What’s more they are blatantly not fair. Spaniards can see there is one law for the 99% and another for the bankers and assorted super-rich elite.

Unemployment, already at 24.3%, is set to deteriorate further. Half of all Spaniards aged between 18 and 25 are jobless – youth unemployment in Spain is now over 50%, like Greece.

Twenty-two per cent of Spain’s population of 47 million are at risk of poverty, a sharp increase since the crisis that hit in 2008, and 1.7 million households across Spain now have no wage earner, an increase of 10% since the start of this year. The Red Cross, which has shifted its humanitarian focus from Africa and Asian to the European disaster zone, helped 1.6 million people in Spain in 2010. Last year that number had risen to two million. And more and more seeking charity are middle class.

Every government forecast for growth issue since Rajoy was elected in a landslide victory against the Socialists in November has been revised downwards. Spain is sliding into its second recession within three years and will be the only country among the 17 nations of the Eurozone set to remain in recession in 2013, according to forecasts, with recovery now several years away.

As no growth means no money for the Exchequer in the form of tax receipts, all this means Spain’s debt problems aren’t going away. To the contrary. And they showing up in the regional governments, which deliver the key parts of the welfare state, including health, education and social services.The Valencia regional government, long run by the Popular Party, has now admitted it can longer fund itself on the markets and asked for a bailout by the Spanish government. Valencia and other regions not only failed to meet government-set deficit reduction targets last year, but actually increased their deficit overall.

The fact is Rajoy’s policies are killing the Spanish economy. And that’s why borrowing costs at the time of writing remained at record levels, as bond yields ultimately follow growth prospects, not the deficit (which is largely a by-product of growth).

Growing opposition to Rajoy, Socialists struggle

Opposition to Rajoy’s approach was confirmed by a poll published in July in El Pais newspaper. This showed 62% oppose the austerity measures and believe they are not helping Spain get out of its crisis, with around a third of Popular Party supporters taking that view too. And 78% of Spaniards say Rajoy inspires little or confidence.

However, if the Popular Party has lost a lot of support since March, the main opposition Socialists remain at a historically low ebb. If an election was held today, Rajoy’s party would achieve 37% of the vote against 23.1% for the socialists. One reason is the Socialist leadership, whose new leader Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba in particular, is seen as out of touch with the anguish and suffering of the Spanish people, and too much a man of the past.

In many ways, the Socialists remain imprisoned by their own recent record. It was a Socialist government who oversaw the banking-fuelled speculative bubble, even if the disastrous banking-bricks-and-mortar model has its origins in the 1960s boom under Franco. Furthermore, in May 2010, after trying to fight the economic downturn by lifting government spending, the Socialists gave into the blackmail of the financial markets and kicked off what has turned into an endless series of austerity budgets.

But unlike Rajoy and his party, Spain’s socialists have never been wedded to the small-state ideology that underpins the austerity fetish, nor do they see the crisis as an opportunity to roll back the state to promote private plunder (with the railways the latest public asset being readied for the privateers).

Radical left on the up

For now, it is to the more traditionally radical politics that many Spaniards appear to be turning.

The Communist-led United Left, which has an altogether more ambitious programme to make the wealthy pay their way, tame the banks and diversify the economy away from its dependance on housing and finance, is now at 13.2% in the polls, up from 8.9% in February.

Meanwhile, unions and a revitalised indignados movement are promising more action throughout the summer. And a very hot autumn.

This was originally published in Tribune Magazine (27 July 2012)

Discussion

No comments yet.