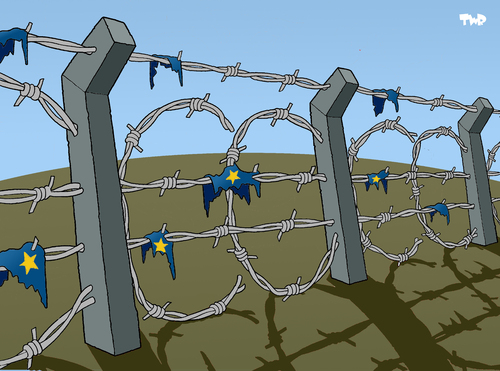

What is the European crisis? One answer is that it makes the privatization of public assets inevitable, delivering big profits for private individuals and organizations. As Greece, Spain and Portugal demonstrates. Europe is being sucked into a downward spiral caused by counterproductive measures, while the crisis carries on its slow, relentless work. Families, if they can, save money, and cut spending. Companies do not invest. Banks are reducing the credit. A crisis of external debt (mostly private) has been dressed up as a crisis of public debt. Public spending is blocked with perfect timing by an international treaty [EU fiscal compact] which imposes the brutal constraints of a balanced budget, without much to distinguish whether it is capital expenditure or current expenditure. It is well known that a policy of compressing public spending, at a time of excess private sector debt and already low – historically low – interest rates could have deleterious effects. The collapse in domestic demand has now reached the strongest economies in the euro area, which is also heading into recession.

Assuming the impossibility of collective madness of all the European ruling classes, one is left wondering who benefits from all this? It is no coincidence that a fashionable recipe to get out of the crisis is the sale of public assets in order to reduce debt. Of course, public finances in a mess, forced to privatize public goods and services, is the classic scene from a film we’ve already seen in many parts of the world. We haven’t got here by chance. It’s one of the barely hidden objectives in strategies of attrition in the public sector to ‘starve the beast’. The beast is the state, the ideological enemy that must be starved of resources. The quality of the services it provides to citizens decreases. The citizen sees it and begins to wonder if it really is worth keeping up with their taxes and poorer public services. Then come the saviours of the country, who buy the company or public service at an reduced prices and extract profits. In the best case scenario, the new owner of the former public service delivers it more selectively and at higher costs to the citizenry. It the worse cases, it cherry picks the best parts, and offloads the remaining unprofitable assets on society, takes the money and runs.

The privatization of health care in the United States has doubled the costs for citizens, excluding a huge portion of the population from any health care coverage. Obama understood the error and the economic and social costs of this process and considers the reversal of this evil trend as the most important of his first presidential term. The experience of the “reforms” in Central and Eastern Europe after the fall of communism teaches us that the privatizations – carried out to generate cash, making public goods for the exclusive benefit of a few individuals, with the first services to be privatized the ones that work best, the family jewels – contribute to a substantial increase in inequality. Other parts of the world, such as Latin America, have had similar experiences in which public goods and services were sold at conditions favourable only for the buyer. It is no coincidence that Carlos Slim, the richest man in the world according to Forbes, owes his fortune to the wild privatizations of the 80s and 90s in Mexico, from the mines to telecommunications.

Now it is the turn of old Europe. Portugal ended 2012 privatizing airports, the national airline, (former) public television, state lotteries and shipyards. In Spain, the privatisation ‘express’ concerns ports, airports, the network of high-speed trains- probably the best and most modern in Europe – health, water management, state lotteries and some tourist centres. Greece has recently been urged to accelerate the process of privatization of goods and services provided so far by the state, as a condition for continuing to receive European aid. In Italy, Mario Monti, shortly before his resignation as Prime Minister, decreed the financial unsustainability of the national health system, explaining the need for “new models of additional financing. The Monti agenda argues that “growth can only be built on sound public finances” and then invites us to continue disposals of public assets. And on the front pages of some newspapers there are those who still see “too much state’ in Monti’s agenda.

Economic theory and past experience teach us that while the privatization of public companies can reduce the deficit in a given year, it creates a significant risk of increasing the deficit in the long run, if the company disposed of is productive. Furthermore, it is not enough that the private management is more efficient than the public, the efficiency gain must also absorb the profit that the private investor necessarily pursues. If the seller (the state) is in a hurry and under pressure to do it, those who buy (private investors) have a clear negotiating advantage, allowing for more favourable terms.

And if the conditions of privatization are more convenient for the private sector, they will be symmetrically be more inconvenient for the public sector, ie the general public. Recent studies show that citizens of countries that have undergone rapid and massive privatization in the 90s are deeply unhappy with the results. The ex-post evaluations are all the more critical if the privatization was carried out rapidly, the greater the proportion of public services sold off (water and electricity in particular), and the higher the resultant level of inequality in the country.

Privatization is the final destination of the journey that Europe and Italy are undertaking. It is essential to discuss this issue openly, if the common good is to be served. What is decided will define the direction that Italy takes after this weekend’s elections.

Sbilanciamoci 21.2.2013

Translation by Revolting Europe

Quite so. It’s only the fringe of Europe, but this is precisely what lies behind Jeremy Hunt’s plot of trying to privatise the NHS in England- which is going on under everyone’s noses. Here in the Netherlands the fully completed private postal system has just undergone its ‘reorganisation’ or in plain language its economising measures. The whole system is a disgrace. A mass of underpaid, demotivated flexible labour and a service that has no actual service (I work in it, so I have direct experience). This sort of thing is the future of all privatised ex-public assets.

Posted by Hans | February 27, 2013, 5:46 pm