Italians are voting again after 14 months under “technocrat” Mario Monti. The outcome of the election in terms of delivering a stable government is uncertain.

Pier Luigi Bersani’s centre-left Democrats have been leading in the polls, but billionaire media magnate Silvio Berlusconi’s right-wing alliance is expected to put in a strong showing as is newcomer Beppe Grillo, the comedian-blogger whose Five Star Movement has been on roll since local elections last year, securing major victories, from Parma in the north to Sicily.

Monti himself has thrown his hat into the ring, but is not expected to pick up many voters.

On the outside left flank is an alliance of communists, greens and radical magistrates, but this “Civil Revolution” was seen trailing a distant fifth.

The prospect of political instability in Italy, accustomed since the end of the second world war to weak short-lived governments, is nothing new.

But this four – perhaps five – horse race is something new. At the start of the year it looked like the Democrats, fresh from a US-style primaries race, were going to easily clinch power.

But since then Monti, who was ruling unelected since November 2011, entered the race.

And Berlusconi, pretty much written off amid deepening legal problems and a disastrous one-year term, bounced back – no little thanks to his continuing monopoly of private TV and the odd best-selling newspaper too.

Then there’s the extraordinary rise of Grillo, Italy’s answer to the Pirate parties of northern Europe – a man who has made it a central feature of his career as a comedian and now politician to expose political corruption.

This is fertile ground in a country that brought us Bribesville in the early 1990s and – fed by a wave of privatisations that’s seen an unprecedented cosiness between business and the political establishment – is just as mired in sleaze today.

Grillo has also won growing support from left and right voters with his direct, some would say aggressive, style and mass rallies, in sharp contrast to the other political leaders who rely on TV. Grillo rejects all press interviews and appearances. In the last days of campaigning he brought half a million to a rally in Rome.

Like Berlusconi, he’s also a Eurosceptic, and has promised to review membership of the single currency, as well as all other international treaties, from the country’s role in the Nato-led invasion of Afghanistan to agriculture and trade pacts.

The rise of Grillo, the return of Berlusconi and Monti’s lacklustre campaign reflects a rejection of what some have dubbed the “Monti agenda.”

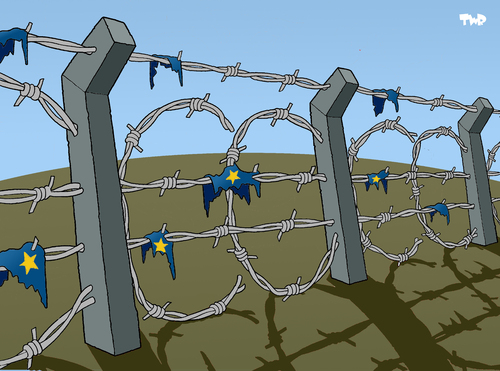

This is that combination of neoliberal reforms and punishing austerity measures encouraged by the IMF-European Central Bank-EU “troika,” such as the hire-and-fire changes to labour law and hated housing tax imposed by the former European commissioner, or the EU fiscal compact passed by the Italian parliament last year. More and more Italians are seeing these kinds of impositions as part and parcel of the European package.

The failure of these policies was highlighted by the latest socio-economic data and forecasts which show pretty much all indicators heading south, from jobs and poverty levels, to credit for the economy and growth.

According to Italy’s employers’ confederation Confindustria, the country’s labour market “sharply worsened at the end of 2012,” with nearly 200,000 jobs vanishing in the last two months alone.

This year unemployment in Italy will rise from 10.6 per cent to 11.6 per cent and keep increasing in 2013, the European Commission forecasts.

Misery is spreading, with real wages in freefall and nearly two million children on or near the poverty line.

Italy’s economy contracted 0.9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2012, more sharply than expected, and the EC revised downwards its forecast for gross domestic product (GDP) to a fall of 1 per cent this year – double the contraction of its previous prediction in November.

Data from Italy’s banking association ABI shows bank loans to families and companies dropped by record amounts in January, despite hundreds of billions of euros of virtually free money chucked at Italian banks by the European Central Bank.

Bad loans rose to €64.3 billion at the end of 2012. The national debt, meanwhile is set rise to a new peak of 128.1 per cent of GDP this year.

This state of affairs is likely to continue post-elections as the most likely scenario is a government formed of the Democrats and relying on support from Monti.

The Democrats have pledged to continue Monti’s neoliberal programme but promised to ensure the burden of austerity is not borne solely by the workers and middle classes. This is a very tall order and remains unconvincing for as long as they rule out a much-needed, wide-ranging wealth tax to tap, for the good of all, the huge private wealth held by the lucky minority.

However, there is a distinct possibility that “populists” such as Grillo and Berlusconi – out for himself as always but brilliant at catching the popular mood – will block the Bersani-Democrats dream team. This has got the EU’s superpower Germany – a target of attack by both of them – and the global ruling class, euphemistically labelled “financial markets,” all jittery.

As for the radical left, now re-formed around one of a string of crusading anti-mafia, anti-corruption magistrates who have gained the kind of popular respect many career politicians lack, their struggle to make headway is in part because of the usual media blackout against anti-system parties. in its bid to covey an unconventional message, the Civil Revolution alliance does not have the kind of profile on the web enjoyed by Grillo nor Berlusconi’s domination of traditional media.

But its instinctive internationalisation also translates into a difficult pro-European message.

To be sure, Civil Revolution wants a “different” Europe, cut free from the beggar-thy-neighbour policies of competitive wage devaluation, privatisation and cuts to public expenditure, institutionalised austerity for the 99 per cent and blank cheques for the banks – a Europe centred around people.

But in what was one of the most loyal EU member states, the scale of the “social massacre” rightly seen as directed from Berlin and Brussels – which just last week won new powers to intervene in member states’ budget-setting – is such that that message is being lost.

More and more Italians are putting their faith in politicians who, whatever their real agenda, emphasise national sovereignty over the super-national and global.

Reframing internationalism so it means something genuinely progressive and popular is a challenge that has been plaguing the left for years. It needs a rapid resolution.

Originally appearing in the Morning Star newspaper

Discussion

No comments yet.